|

|

|

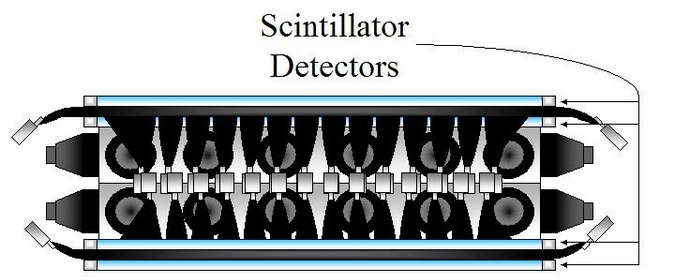

The scintillator detectors in TIGER are

responsible for determining the charge of a particle that passes

through the instrument. Since the particles the pass through

TIGER have a lot of kinetic energy, we can assume that there are no

orbital electrons in the incoming atom. For example, if an iron

nucleus passes through the instrument, the scintillator will only "see"

the 26 protons that are in the nucleus of the atom. Since iron is

the only element that has 26 protons in its nucleus, we can tell from

the scintillator, with an extremely reasonable degree of accuracy, that

the particle that entered was in fact iron. |

|

|

|

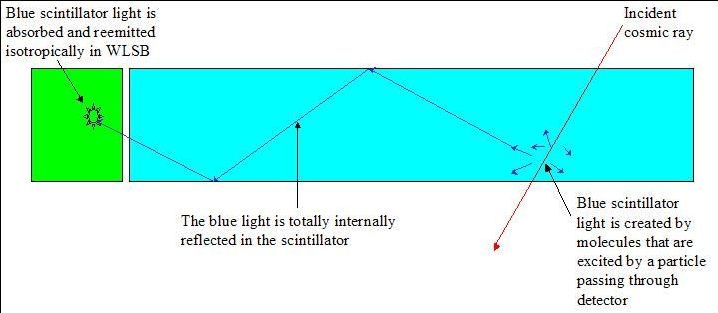

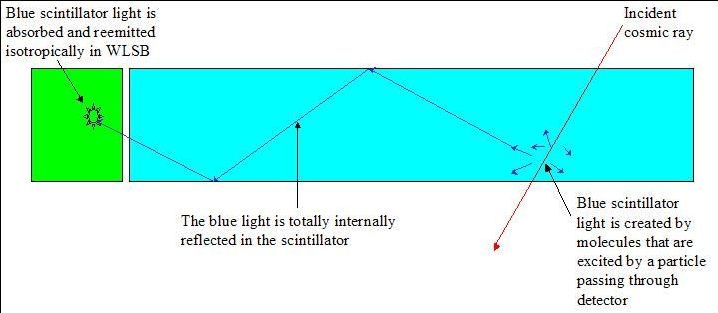

The scintillator is made of a special kind of

plastic called poly-vinyl toluene (PVT). When a charged particle

passes through the PVT, it excites and ionizes the molecules in the

plastic. In so doing, electrons in the PVT molecules move up to

higher orbital energy levels and release a bluish light as they drop

back down. The PVT is designed so that the light that is emitted

inside the plastic is totally internally reflected. The light

bounces up and down inside the PVT until it reaches the end. Here

the light is able to escape out the side of the scintillator, where it

enters another piece of plastic known as a wavelength shifter bar

(WLSB). This process is shown in the figure below. Once

inside the WLSB, the wavelength of the blue light is shifted to green,

continues to reflect internally inside the WLSB, and is piped down to

the photomultiplier tubes on either end of the WLSB (see photo

above). In this way, only 8 PMTs (2 on each corner) are needed to

read out an entire

~1 m2 panel of PVT. |

|

|

|

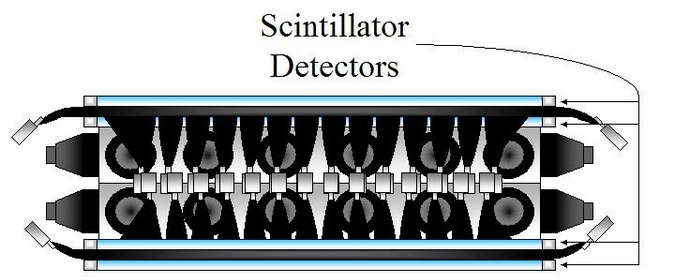

In TIGER, there are four scintillating

detectors, S1, S2, S3, and S4. It is good to have this kind of

redundancy when building particle detectors. The sum of the

signals from several scintillator detectors is always better than just

the signal from one of them. Furthermore, if one or more of the

scintillator detectors fail, the experiment will only suffer a

handicap, not a total failure. The S1 and S2 scintillators are

the most important for deriving the charge of a particle.

Coincidence in the detector is also determined by the scintillator

detectors. If the signal in the required detectors is high

enough, the software decides that a particle has indeed passed through

the detector, and proceeds to read out the light output. For this

and the last TIGER flight, the following coincidence pattern was

used: (S1 OR S2) AND (S3 OR S4). |

|

|

|

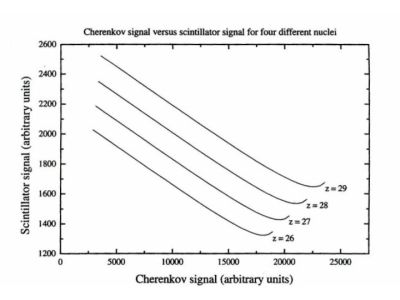

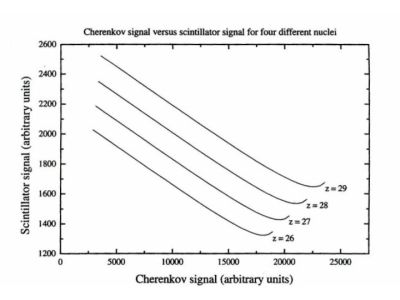

The plot above shows what the

scintillator signal (dE/dx) would look like when plotted against the

Cherenkov (energy) signal. As the energy increases from 0, the

scintillator signal drops rapidly at first. However, as the

energy of the incoming nucleus reaches relativistic proportions, it

becomes a minimum ionizing particle (MIP) and the scintillator once

again begins to respond. The signal that a certain nucleus

creates in the scintillator is highly sensitive to its charge, as was

discussed before. The scintillator signal, while also somewhat

sensitive to the energy of the particle, is proportional to Zn,

where n

is between about 1.5 and 2. Looking again at the plot to the

left, as

more and more particles trigger the detectors, charge bands will begin

to form in the data. Here we see where the contours of Fe, Co, Ni

and Cu would lie with respect to one another. |

|

|

|

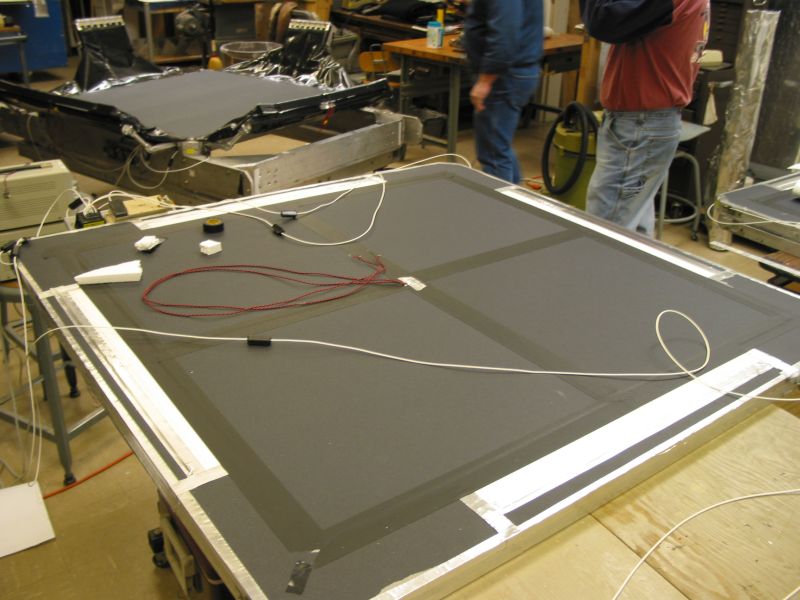

One of the TIGER scintillators, all ready to go

|

|

|